Edward Mikkelsen learned a valuable lesson from his former business associate. Mikkelsen, an immigrant from Denmark, moved to Chicago in 1879 to take care of his sick brother, and made a comfortable living as a cabinet maker. He started his business, Edw. Mikkelsen & Co. in 1882. By the 1890’s, a well-established Mikkelsen, partnered with John Gabel, a young inventive and ambitious Hungarian immigrant. They formed the Automatic Machine Tool Company in 1898. Gabel was an early developer of slot machines and music boxes, think ‘juke’ variety (possession of a Gabel model today, slot or musical, would gain you a small fortune). Mikkelsen provided the capital and cabinetry to house the machinery for each unit. Within a year, the two decided to part ways over, among other things, the importance of advertising. Mikkelsen espoused that the machines should sell themselves while Gabel believed people can’t buy what they don’t know exists. Mikkelsen wanted out and sold his interest to Gabel but he kept the right to provide cabinets. It seemed like a smart move for both parties.

Mikkelsen certainly realized his mistake as he watched Gabel find success. Although, he still supplied the cabinetry, he knew he erred in his business strategy. He acknowledged the need to advertise. When he applied this strategy to his new game making venture, he unwittingly established a legacy of producing the most visually pleasing crokinole advertisements and boards ever created.

‘The Owl’ takes flight

Edw. Mikkelsen & Co. offered two styles of board referred to as No.1 and No. 2. No. 1, the top model, offered 100 games of play and was adorned with beautiful graphics, specifically owls that gave the board its less generic namesake, The Owl Combination Game Board. In 1903, The American Stationer (Vol. 54), a marketing publication, described the board as “one of the most artistically designed and popular boards on the market” and “handsome, decorated in bright colored marquetry transfer work…”. No. 2 had less frills graphically and less games (75) and was the more economical alternative. No. 1 had more pieces (109 vs 60). The most notable additions were table legs, dice and pawns. Both came with a revolving stand.

Each board included The Owl Game, a carroms-style game, whose rules deliberately avoided using that term. The year 1902 marked the publishing date of the Owl rule pamphlet, it was also the year that Ludington Novelty Company (eventually the Carrom Company) sued the Leonard Game Company over the use of the term ‘carroms’ (Ludington Novelty Co. v. Leonard, 119 F. 937, 1902). The case centered on whether ‘carroms’ was a generic term or one that could be protected by trademark. It looked like Mikkelsen decided to stay clear of the conflict by creating an alternative to the title carroms.

It was typical of combination board manufacturers to one-up their competitors by stretching out the number of games offered by counting slight rule variations as separate entities. For example, The Owl Game accounted for five games based on tweaks to the basic rules. Other games of note included Old Mill (Nine Men’s Morris), pool, several pin oriented games and an interesting fortune telling game loosely based on the way that runes are used for prognostication. Entries 75-100, unique to Board No. 1, included games like the Star Game (similar to Sorry or Pachisi), point-centered games, most notable Backgammon, and Fox and Geese. Again, variations helped stretch the count to the century mark.

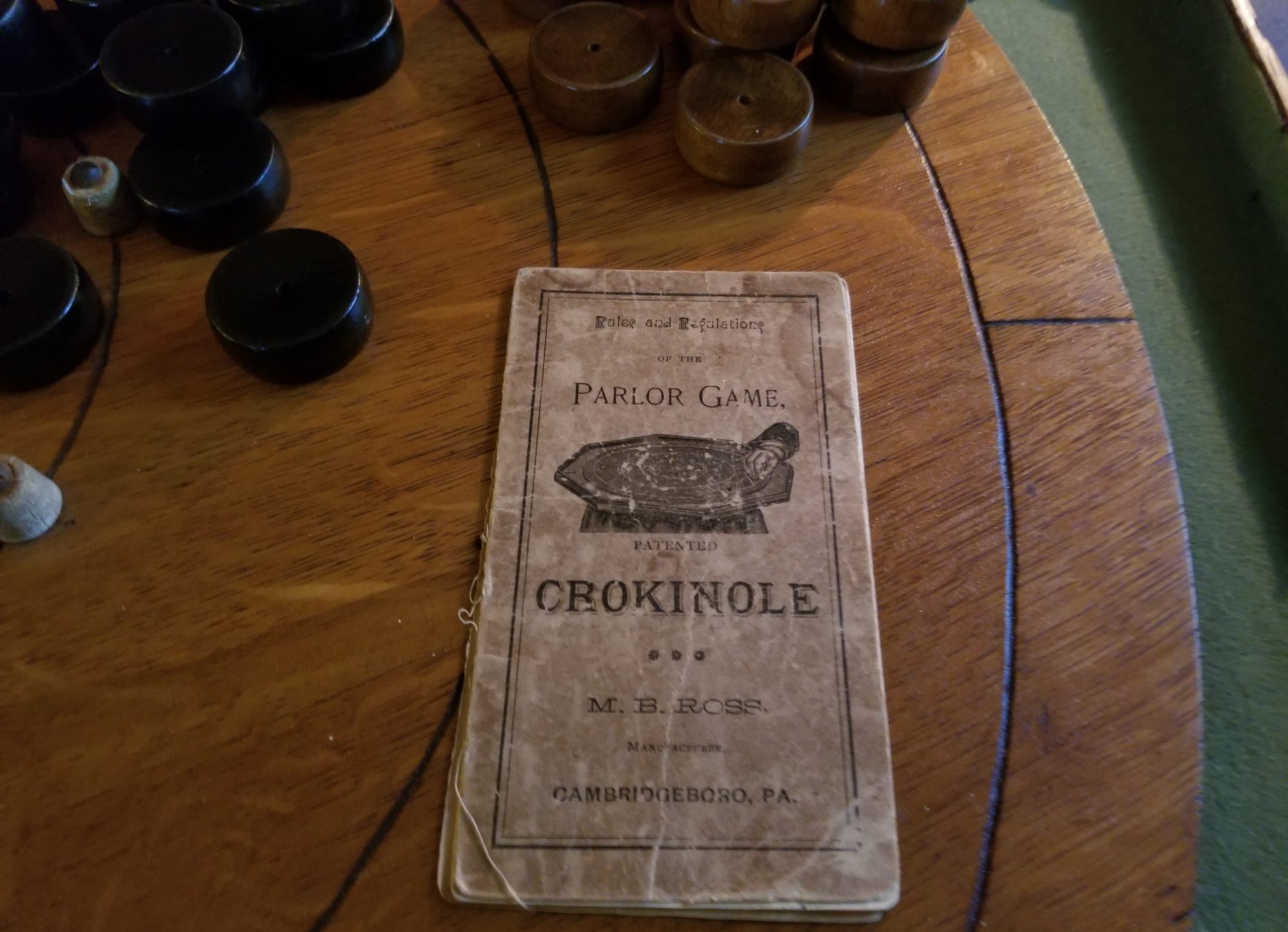

A somewhat unique feature of the Mikkelsen boards, is the use of wooden posts. Each is hollow with a screw placed in the middle to secure it to the board. Contemporary manufacturers like M.B. Ross, Archarena, and Carrom used rubber. Mikkelsen went so far as to protect this improvement by patenting it in 1906, but had applied for it as early as 1903. He cited that rubber ‘pins’ were costly, did not last as long nor produced any sound when hit by rings. Where’s the fun in that? Some contemporaries like the Leonard Company used wooden pegs and eventually the Carrom Company transitioned over as well.

Why the owl moniker? Other companies used interesting graphics, but they were usually associated with game play; the Carrom Company incorporated designs on their crokinole boards to designate quadrants and scoring rings. The owls on the No. 1 board played no such role and were soley there to enhance the beauty of the board and to demark it from its competitors. It was only fitting that the remarkable owls surround the crokinole playing surface since the game was the main feature of these boards. When viewing the No. 1, the owls and crokinole center command your attention and makes it one of the most striking models ever produced.

Interestingly, the owl name and imagery were used by gambling machine maker, the Mills Novelty Company, who Gabel worked for, and by Gabel himself, when he began making machines, when he set out with Mikkelsen. Mikkelsen who built the cabinets, knew the machine names and saw the graphics being used, and must have liked the images too and used them for his games. Since there wasn’t any direct competition between a slot machine designed for saloons and a family oriented parlor game, there was probably no issue in its use. Mikkelsen’s versions include cues and rings, acting as a perch for the owl.

He gets a lot of mileage out of the owl. There are four located on the crokinole side of the No. 1 board, and a more crudely designed owl is stenciled on both styles of boards. Owls appear on the rule books and in many of the ads. Although he changed his ways and adopted advertising, he did hold unto his belief by making the boards aesthetically pleasing, so they could sell themselves as well.

What happened to the Owl Board and Edward Mikkelsen? He produced other games, most notably the Owl Hockey Game (I would love to discover one). I did not find any other crokinole variations beyond the No. 1 & 2 boards. He advertised in several papers in the early 1900’s. I found examples ranging from 1901-1907 in newspapers in cities like New York and Boston and states like Kansas, Iowa, South Dakota, Wisconsin and Nevada. Being centered in Chicago gave him great reach to market and ship his games, and the city itself offered plenty of customers.

Soaring with Sears Catalogs and Games

Then there is the Sears conundrum. The massive retail giant and catalog king seemed like the ideal means to sell product…if you could secure a place in the book. They offered vast exposure through their catalogs while receiving favorable shipping rates due to their volume. Securing space would be a manufacturer’s golden ticket The fact that both Sears and Mikkelsen were located in Chicago made the opportunity to deal more realistic.

Sears had reason to be interested. There was a crokinole boom in the 1890’s in the US. Sears started offering boards in 1899, a combination board called Bombardo and a basic crokinole-style board (MB Ross board?). Starting in 1901, Sears had their own brand of combination crokinole board under the name Seroco (Sears Roebuck and Company). This selection of boards lasted until 1903. From 1904 through the Spring of 1910, the Seroco was the only game in town. This changed in the fall of 1910 when the Owl Boards appeared by name in the catalog and then again in the spring of 1911. Mikkelsen struck a deal.

However, it was short-lived. By the fall catalog of 1911 and through the spring catalog of 1913, the Owl Boards suddenly changed their names. There were two boards for sale called the Perfection Reversible Combination Game Board and the Monarch Combination Game Board. Based on the images, these were clearly Owl Boards No. 1 and No. 2. The write-ups were essentially the same and the owl imagery was noticeable in the illustrations. On a positive note, the boards were cheaper.

What happened? Did Mikkelsen sell the rights? His factory suffered a fire with a total loss in May of 1911. A devastating fire, it caused $100,000 in damage, destroying a piano manufacturer who shared the building and killed a fireman. By June he and the piano company found a new building with 30,000 square feet of space and leased it for 5 years at $35,000.

Did he decide to sell rights to Sears and his remaining stock and focus on his cabinetry production? This part of the story is not clear. Mikkelsen boards last appear in the Sears Catalog spring 1913, the last owl-style board, under its new name, is advertised. The fall of 1913,introduces Carrom Company boards, the illustrations clearly show the classic board line. Once again the company and board names are not mentioned specifically. Owl flew the coop.

The end of the owl trail is not the end of Mikkelsen. He continues with cabinetry making with such items like a cabinet for soiled towels which appears in an ad from 1915. He takes out a patent in 1918 for a door catch. There may be more examples of his endeavors. Edward died in 1926 in Chicago and is buried in the Mount Olive Cemetery of that city.

Loose End

I found online an old auction for a Seroco box that contained the pieces for the board. The box had a picture of a family playing games which is the exact scene used by Mikkelsen in his rule book and ads, going back to 1902. The Seroco board itself is also very similar in style, construction and graphics (minus the owls) to the Mikkelsen boards. Did Sears copy his board and imagery prior to selling the Owl Board? Did Mikkelsen use this to his advantage, threaten a lawsuit, and this being the reason for Seroco’s disappearance and the Owl substitution in the catalog in 1911 ? Did Mikkelsen produce boards for Sears to sell under their own branding? Regardless, it is peculiar that the Owl Board is sold by Sears after it discontinued its own board, a board so similar. Hopefully answers will present themselves one day.

Legacy

As a crokinole fanatic, I find that most boards, even the most utilitarian examples offer something in craftsmanship or artistry. While many mass produced boards started losing artistic touches to maximize game choice and probably profits, Mikkelsen created a board that commanded attention while offering variety. Mikkelsen did learn from his prior partner that advertising is important and was able to hitch his star to the Amazon-like Sears, but he also created a board that could truly sell itself. When crokinole board makers today use striking graphics and consider the artistry of their craft, they are following in the steps of Mikkelsen.

*A special thanks goes out to Rick Crandall whose research on John Gabel allowed me to see a glimpse of Edward Mikkelsen. Check out his work on slot and music machines at https://www.rickcrandall.net/ Sources for other information in this article will be shared upon request. Boards and rule books in images are my own.