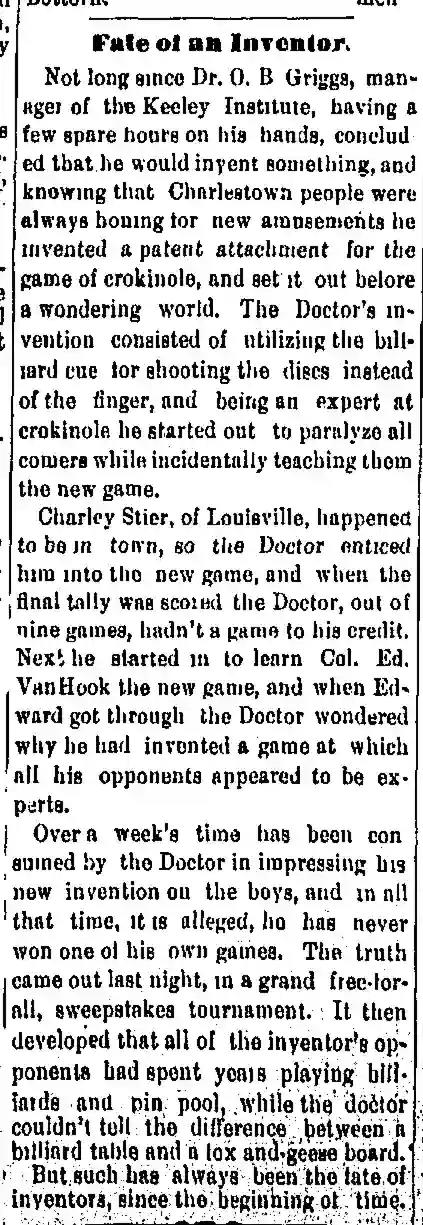

An impactful primary source can often speak for itself, but this article leaves one a bit confused. Currently on Facebook there is a discussion about the role of cues in crokinole. Typically they are used by Canadian players who need greater board access and for ease, compared to the limited range of finger flicking a disk. I’ll allow the discussion online to elaborate on its place and who should use them, but I wanted to add my take by, as usual, looking at the past.

I found this piece and thought it would be a straight forward cut on the origin of cues but nothing is easy. When I looked up cues and O.B. Griggs in a patent search I found nothing. I assumed since the article mentioned patent, an inventor and invention I would find it. Nope. So it goes… While the article is interesting and adds some cheekiness and humor to the subject of cues and the angst of many an inventor who birthed an idea but quickly lost control (Hello Nobel!), it doesn’t align with the historical record of those who have actual patents for tools to project disks across a crokinole board. I think this article is more of a case of Griggs appropriating a pool cue for crokinole use just like I appropriate a spatula for a backscratcher.

This may not be a comprehensive list, but here are some highlights of notable ‘cues’ to give your fingers a break that have been recorded by the US Patent Office.

Robert C. Moore of Illinois patented this toy cue (above) in 1898 as a means to improve accuracy and alleviate the pain of finger flicking in crokinole, carom and archarena. These are his words found in the patent description as the reason behind his invention. A side note, this topic comes up often in early crokinole references. People do complain about their fingers hurting. Companies do counter by boasting their wares as finger-friendly. For example, the Carrom Company claims that their rings are easier on the digits than traditional disks. In our crokinole ancestors’ defense, disks produced in the 1880s and 1890s were hefty. They were the size of the round piece found in tinker toys.

1880/90s vs Modern

Finger Friendly 1899 Ring

Louis Eickelberg of Iowa received his patent in 1903, for my personal favorite, the Carom Gun. The patent states it is for crokinole, carrom and ‘kindred’ games. This attaches to a pencil (you provide) and the coiled compression of the spring provides the force.

Julius Clark also tried to save humankind from another broken fingernail according to the patent of the Crokinole Cue of 1916. This cue too used a coil device to create propulsion of disks for both crokinole and carrom.

William Virnig of Minnesota found another way to make a patentable device to project pieces for carrom and crokinole with his game cue. There’s no pretense to saving fingers or nails from fractures, aches or pains in the patent write-up. Just a straight shooting cue for improving your game play.

Overall I do think it curious that these improvements all come from the mid-west of the US with Indiana, Illinois, Minnesota, Kansas, and Iowa represented. I am also curious how much force all these different devices provide for moving pieces across a relatively shot distance. Perhaps users were warned vis-a-vis the Red Rider BB Gun that they would shoot their eye out which we know from the Eisenhowers can actually occur playing crokinole (see my Facebook post).

The whole cue progression in the patent world is similar to the develop of crokinole game boards in the US in the 1890s and early 1900s. Overall, American entrepreneurs and inventors overcomplicated crokinole and carrom by adding as many games and pieces as possible to a set. The cue patents attest to this trend. To their credit, the cues attached to these sets were simple pieces of wood. The cues were primarily added to play carrom but they probably migrated rather naturally to the crokinole side as well. Here are some examples of cues included with American game sets:

In the end, I think Canadian practicality and pragmatism won the day and people fastened cues from pieces of wood or borrowed the idea from carrom/combination sets. They needed an extension to shoot their pieces. And while cue patents arose, people eschewed them and their coils, springs, pencils and pretense.